FLESH FIXTURE FEELING: Written by Elliot R. Engles

I have a fixation with bathrooms.

It is hard to say exactly when it began. For narrative’s sake I should say that the fascination stems from when I was a young girl who ducked into men’s rooms to investigate the urinals—an object made libidinal by its forbiddenness. I should say it came about when I stalked my ex-lover’s instagram as they collected and shared photos of toilets they had pissed in during a cross country road trip, imagining that if we were still together I might guard the bathroom door from transphobes.

In actuality it is quite a new fixation, born from an adult fascination and perversion. I drew my first toilet in a panic in 2023, egged on by the pressure of my masculinizing body, which finally allowed me access to the urinals, even as I remained (and still remain in perpetuity), unable to interact with them. Instead I should walk casually past them, open the door to the stall and lock myself out of sight. And yet I still fear the glance through the gap in the door which will reveal that I am a trespasser in the space.

Upon entering Flesh, Fixture, Feeling I am no trespasser.

The collection of works by Elliot Doughtie, Danni O’Brian, and Olivia Zubko are not porcelaneous, sterile forms as I had expected from the “bathroom show” that I was promised and seduced by. I expected there to be a certain uncleanliness implied in the objects, a fixation on the abject. I was ready to ruminate on Ernest Becker and his treatise on human’s ultimate fear of mortality, The Denial of Death, in which he argues that anality, or the fact that humans must shit, represents the greatest hurdle to our triumph over nature. He writes;

Excreting is the curse that threatens madness because it shows man his abject finitude, his physicalness, the likely unreality of his hopes and dreams. But even more immediately, it represents man’s utter bafflement at the sheer non-sense of creation: to fashion the sublime miracle of the human face…. And to combine it with an anus that shits! It is too much. (1)

It is this terror, this disgust with and fear of death, that produces the association of the anus (and thus the bathroom) with uncleanliness. The transgression of hierarchy—a reminder that humans are not fixed above other living creatures—disturbs our identity, undermines our naturalized assumptions about the world, and creates the sensation of revulsion (2), which is what I expected to see explored in Flesh, Fixture, Feeling. It is not, however, what I found.

Instead, the scandal of the objects is not that they are disgusting, but rather that they are horizontally erotic—that they flirt, rather than wrestle, with death.

What connects the work of Doughtie, O’Brien, and Zubko is not that they borrow the aesthetics of the bathroom, but that they are invested in what Leo Bersani might refer to as a “radical disintegration and humiliation of the self,” (3) borne from a celebration of erotic powerlessness, a rejection of both moral hierarchy and the dissolution of said hierarchy. (4) There is a pleasant sort of abjection present in the show, one that takes note of the cyclical nature of the care and keeping of the self and that plays with the inherent libidinality of the bathroom—a mundane place in which we continuously confront that our bodies are not isolated objects, but systems which are penetrable, leaky, and constantly in flux in Harroway-esque (5) fashion. Flesh, Fixture, Feeling does not aim to confront mortality, but rather invoke a sense of cycles. Of maintaining the body and life through ritual. Rituals of purification, of expulsion, of reproduction, sequestered away from (or, in the case of Doughtie’s work, furtively exposed to) the watchful eyes of the public.

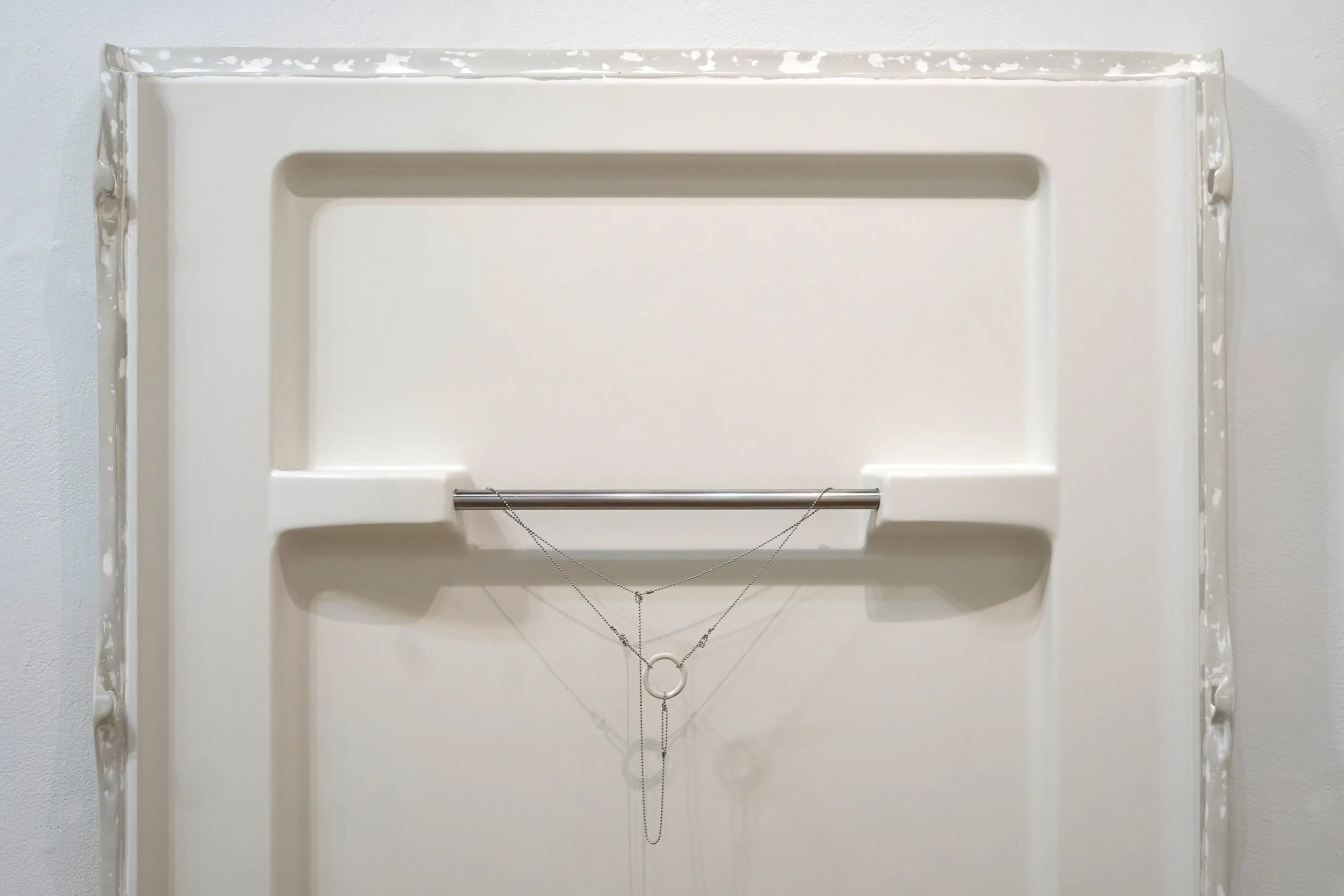

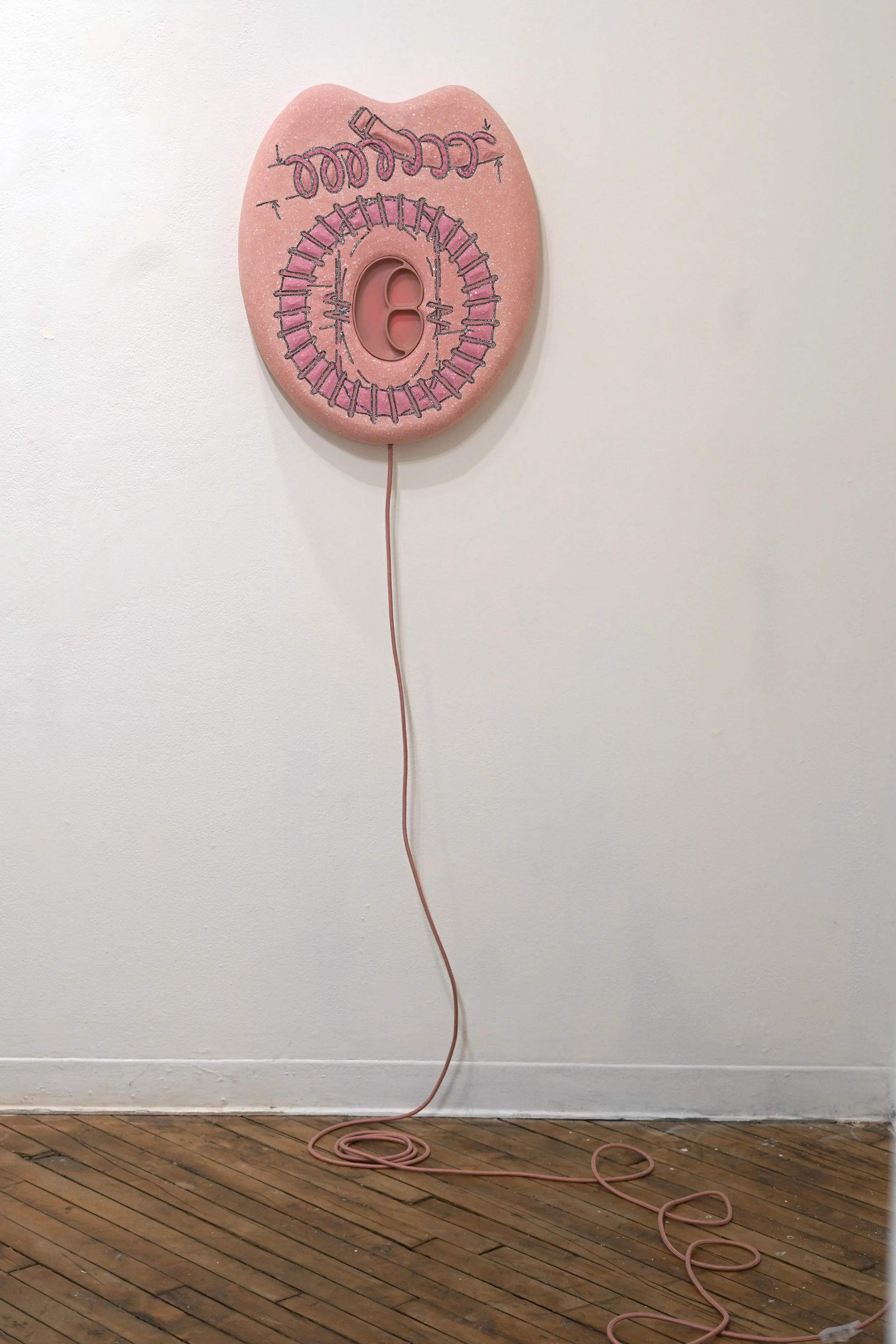

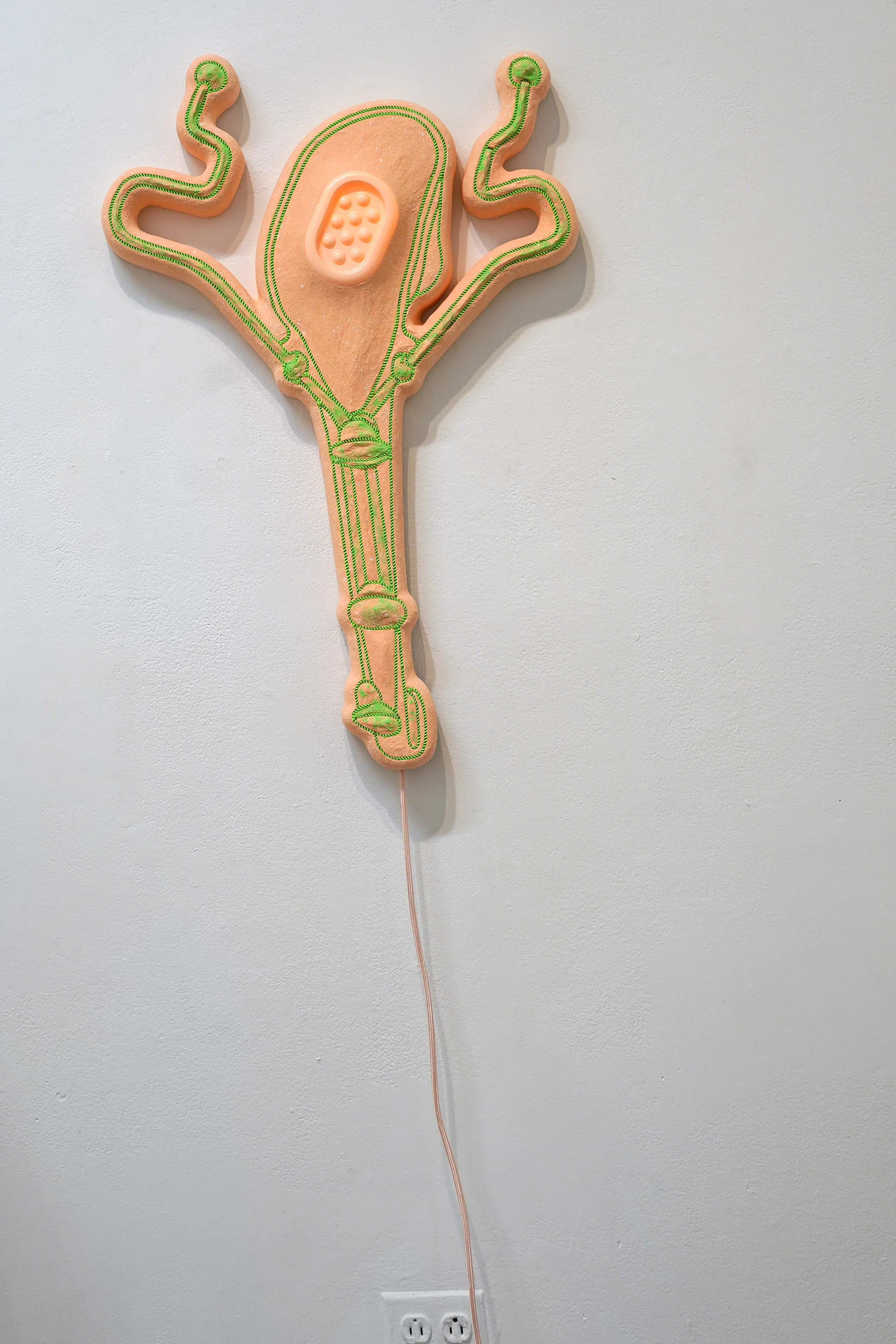

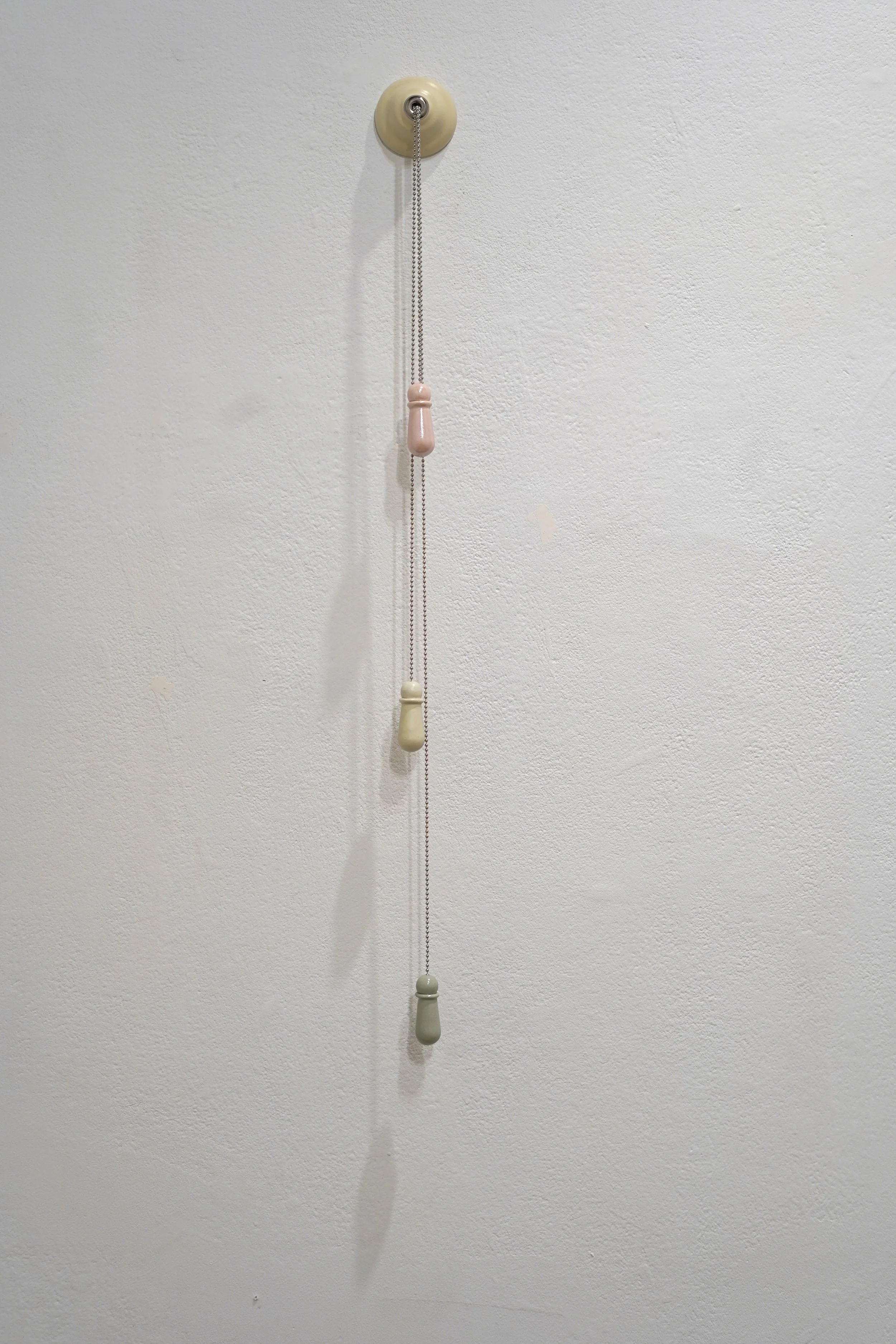

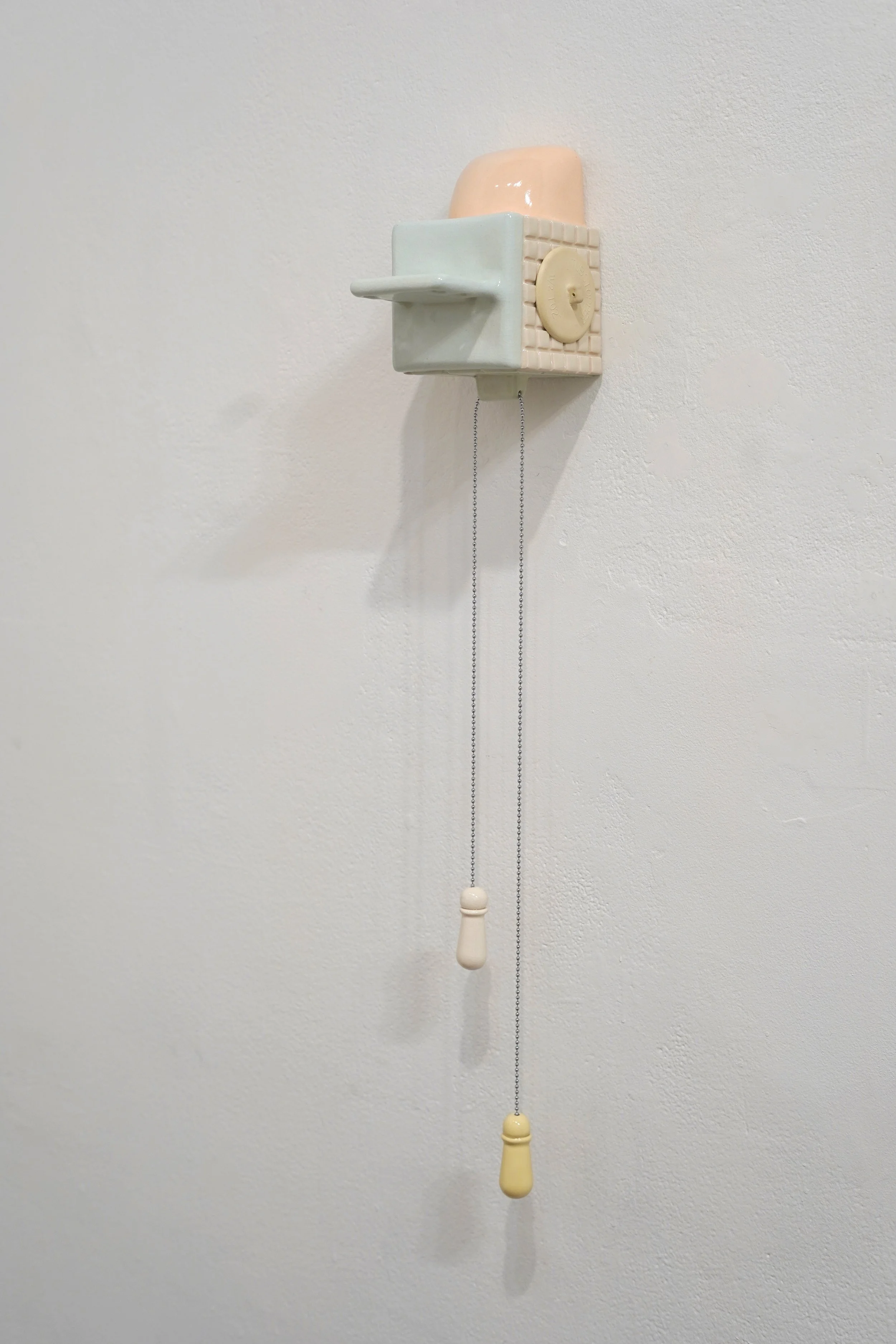

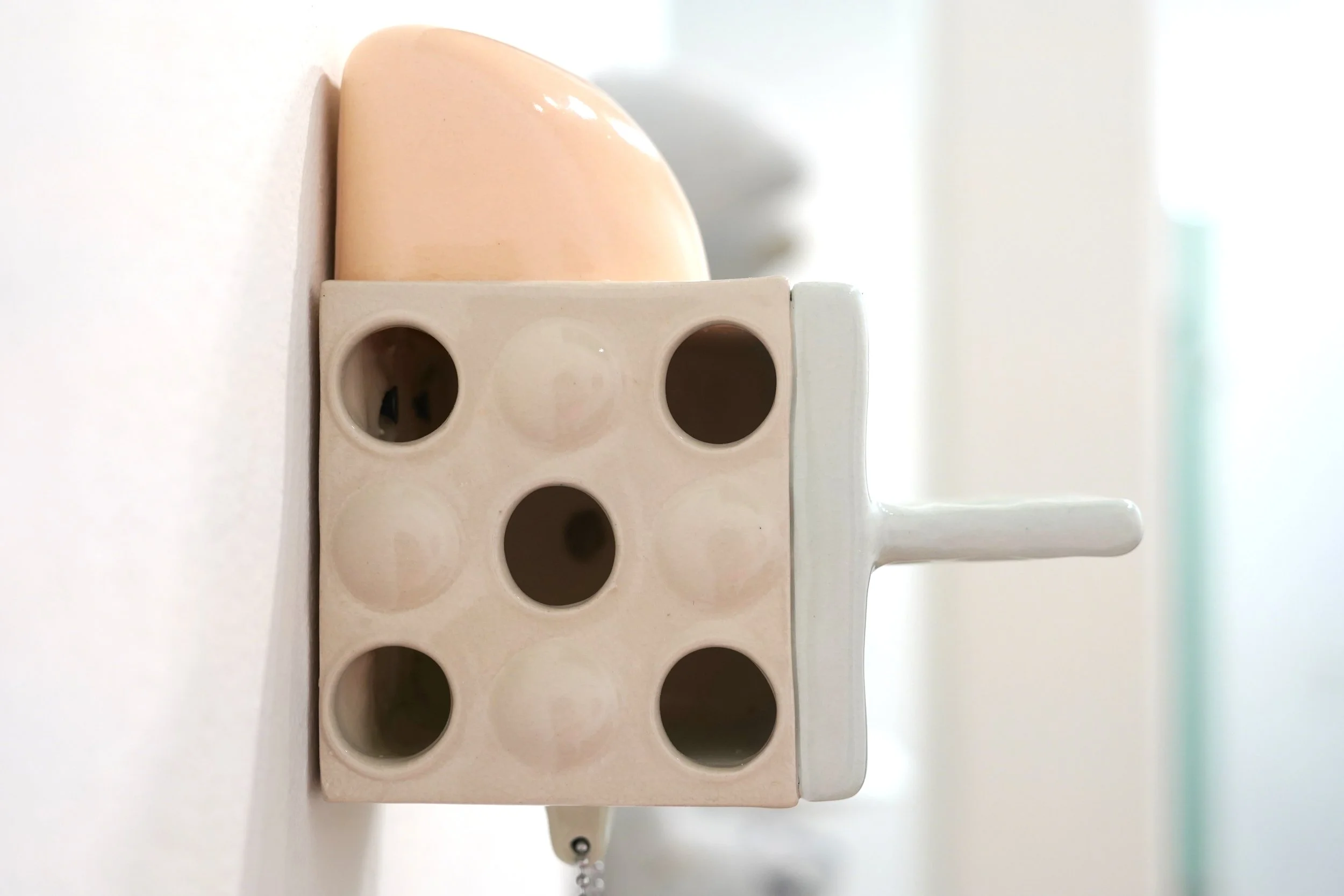

Zubko’s porcelain contraptions, which might do triple duty as a drain, a soap holder, a pull chain which, upon activation, could do anything (or nothing)—could drain, flush, or pour water of a dubious origin onto my head. They are clever little objects that evoke the ways plumbing becomes an extension of bodily functions through hidden architecture, the bathroom a place that we return to time and again to maintain ourselves. The viewer becomes an implied bather, both literal and a figment of art history, invited to step into the role usually reserved for the object of the gaze, rather than the executor of action. O’Brian’s cyborg assemblages, which feel all at once like concrete and tufted rugs, are familiar and strange as they take on the form of an alien uterus and fallopian tubes, or a blushing pink ring that evokes a condom, a hormonal ring, a birth control pack. “Blink, blink,” O’Brian’s objects seem to say, and I am reminded of Paul Preciado’s edible panoptocon—the contraceptive wheel stored in a little faux-makeup compact and carefully formulated to prevent pregnancy without forfeiting femininity. (6) Except this birth control is not edible, but insertable, boofable, and wifi-accessable. It is Doughtie’s work that speaks in a most delightful way, to my own preoccupation with the public bathroom. A delicate metal chain with a suspended ring becomes a discarded strap-on, invoking the locker room fantasy of an erotic encounter. A stall door with razor sharp teeth threatens to draw blood if I dare enter, a reminder of the equally terrifying and arousing potential of daring to piss in in public while occupying a trans body. These works evoke the viewer’s fleshy softness, our penetrability (made most poignant by a pair of yawning/yonic vampire fangs, which threaten to both bite…) and our subsequent leakiness (... and suck).

Throughout it all is the lingering presence of the vagina dentata, not one that castrates, but rather nips playfully. A stall door becomes a cavernous mouth, a cyborg pussy could titillate or terrify, a hemorrhoid pillow regards me with naked (oh!) indifference. Orifices that open, wink invitingly, only to teasingly snap their jaws closed before the phallus, fingers, tongue, suppository gets too close. Bersani says that parody is an erotic turn-off. Bataille laughs: JESUVE! Jesuve - what a scandalous image! (7)

A lover of mine described urophilia as a “politically burdensome” fetish. I think holding any investment in the bathroom—the toilet, the shower, the stall, the urinal—is politically burdensome today. The bathroom, like the body, is an ideological battleground, rife with government overreach especially now, as we feel the grip of our own bodily autonomy slipping away. Doughtie, O’Brian, and Zubko wrestle it back. Flesh, Fixture, Feeling is not a rumination on death or fear or mortality, but more so a treatise on the ways that the bathroom is an extension of life, reproduction, and pleasure. A site of eroticism, pain, and sweet humiliation.

1. Becker, Ernest. 1973. The Denial of Death. S.L.: Free Press.

2. Kristeva, Julia. 1982. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press.

3. Bersani, Leo. 2009. Is the Rectum a Grave? : And Other Essays. Chicago: The University Of Chicago Press.

4. ibid.

5. Harroway, Donna. 1991. “A Cyborg Manifesto.” In Simians, Cyborgs and Women. New York: Routledge.

6. Preciado, Paul B. (2008) 2013. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. New York, N.Y. Feminist Press.

7. Bataille, Georges. 1931. The Solar Anus. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/georges-bataille-the-solar-anus.

Writer Bio:

Elliot R. Engles (B. 1996, Memphis, TN) is a painter, writer, and multi-disciplinary artist based in Philadelphia, PA. They hold a BFA in Studio Art from the University of Memphis and in 2024 received their MFA in Painting from Tyler School of Art and Architecture. Increasingly, Engles finds themself creating according to where the wind blows them—whether it be performing interpretive dances to opera songs while wearing a paper mache bull head, torturing and crucifying Barbie for her transgressions against feminism, or painting disembodied porn angels as they use the toilet. Regardless, the core themes of gendered embodiment, identity construction, and the permeability of the barrier between self, other, and environment, remain central across all of their projects.